What Is Autism? Signs, Profiles, and Life Stages Explained

June 23, 2025

Autism or Autism Spectrum Condition (ASC) is a lifelong neurodevelopmental difference that affects how people perceive the world, communicate, and relate to others. Autism can affect communication, social interaction, processing, and sensory perception.

While many associate autism with social challenges or rigid thinking, it’s important to recognise its breadth and depth. People on the autism spectrum often experience heightened sensory awareness, a preference for clear, logical patterns of thought, and a strong need for routine and planning.

With increasing awareness, there’s growing recognition that autism presents differently across genders, life stages, and personal contexts. This blog explores autism across age and gender, common misconceptions such as demand avoidance, and how autism intersects with wellbeing, health, and societal challenges. Grounded in a strength-based understanding, we aim to foster clarity, acceptance, and self-understanding.

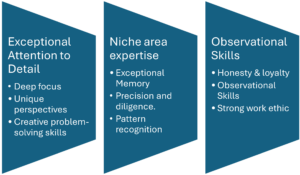

Autistic individuals may display exceptional strengths in areas such as attention to detail, visual processing, creativity, technical understanding, and problem-solving. Many are recognised for their integrity, sincerity, and deep loyalty. The way autism presents is shaped by individual traits and environment—not all autistic people will experience the same challenges or strengths.

As a result, effective support must be tailored to the individual. A one-size-fits-all approach often overlooks both the subtle difficulties and the unique abilities that autistic people bring. Recognising personal strengths, communication styles, and sensory preferences is key to fostering self-understanding and long-term wellbeing. In this article, we aim to demystify autism by exploring how it presents in different people, the support that can help, and the social changes needed for genuine inclusion. Autistic people are entitled to the same human rights as anyone else, yet often face discrimination in healthcare, education, and employment. The UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities recognises neurodivergence under disability protections, including reasonable adjustments.

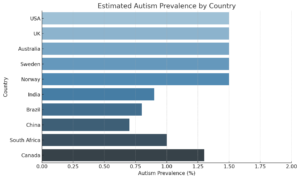

Understanding autism is essential for creating inclusive workplaces, classrooms, and healthcare systems. About 1% of the global population is estimated to be autistic, yet many environments fail to accommodate their needs. Greater understanding improves accessibility, reduces stigma, and empowers autistic individuals to thrive. Embracing neurodiversity unlocks talent, loyalty, and creativity that benefit everyone.

Table of Contents

- What Does Autism Look Like in Females?

- How Does Autism Present in Males?

- Understanding Autism in Teenagers

- Recognising Autism in Children

- How Many Types or Profiles of Autism Are There?

- How Many Autistic People Are There Worldwide?

- How Does Autism Affect Employment?

- Is Autism Linked to Pathological Demand Avoidance (PDA)?

- Does Autism Impact Physical and Mental Health?

- Is There a Connection Between Autism and Anger?

- Is Autism Linked to Criminal Behaviour?

- How to Know If You’re Autistic: Signs, Tools, and What to Do Next

- Frequently Asked questions

1. What Does Autism Look Like in Females?

Autistic women are often overlooked due to masking, which is the unconscious or conscious suppression of traits to fit in socially. Many receive diagnoses later in life, after years of mental health challenges. High-masking individuals, those with strong verbal skills, or people socialised to ‘fit in’ often go undiagnosed for decades.

Late-diagnosed women report struggles with identity, chronic burnout, and internalised shame. Progressive understanding emphasises creating safe environments where women can unmask and find community. A recent UK phenomenological study by Lynch, Murphy & Da Cruz (2024) explored how late-diagnosed autistic women describe their occupational identity. Interviews highlighted themes of “disconnection from one’s own volition”, “striving for occupational balance”, and “acceptance as a protective factor”—underscoring the profound personal impact of receiving a late diagnosis.

Experts now understand that autistic masking, while socially adaptive, can come at a high emotional cost—contributing to anxiety, exhaustion, and delayed support. Tailored assistance can help autistic women recognise safe environments, understand their own needs, and rebuild confidence to unmask and express themselves authentically.

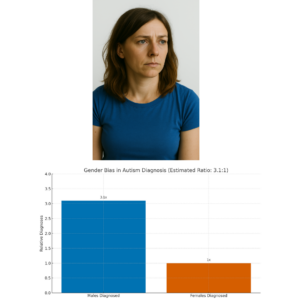

Traditional estimates suggested that males were four times more likely than females to be assessed for autism. However, more recent UK studies suggest this ratio may be closer to 3.1:1, indicating a narrowing diagnostic gap.

2. How Does Autism Present in Males?

Historically, autism was studied primarily in boys who exhibited certain sets of traits—such as overt repetitive behaviours, narrow interests, and minimal eye contact. These early studies heavily influenced what became the ‘gold standard’ autism assessments. As a result, many diagnostic tools still reflect a narrow understanding based on male presentations.

Autism in boys has been more widely recognised and studied, reinforcing these diagnostic norms. Traits such as visible stimming, intense focus on specific interests, and emotional shutdown are more likely to be identified in males. However, we still do not know how many men also mask their traits or are assessed late—or not at all—due to this historical bias.

While boys may be identified earlier, they still face social pressure, confusion about emotional norms, and frequent misinterpretation of their behaviours. Tailored strategies include recognising their strengths in logic, visual reasoning, and technical skills while offering support in emotional expression.

3. Understanding Autism in Teenagers

Teen years present particular challenges due to increasing social expectations, identity development, and sensory changes. Autistic teens may experience increased anxiety, social exclusion, and school avoidance.

Supportive environments that reduce pressure and affirm neurodivergent identity are essential. Peer groups, flexible learning options, and understanding teachers can make a big difference.

Teen years present particular challenges for autistic individuals, marked by growing social expectations, rapid identity development, and hormonal and sensory changes that can heighten sensitivity. This period often brings a sharper awareness of difference, which can lead to increased anxiety, low self-esteem, and confusion about social roles.

Many autistic teens struggle to keep up with shifting friendship dynamics, unspoken rules, or the demands of secondary school life. As a result, they may face social exclusion, internalise a sense of not belonging, or begin to avoid school altogether—sometimes leading to prolonged periods of disengagement or burnout.

Supportive environments that reduce pressure and affirm neurodivergent identity are essential during this stage. This includes creating space for teens to explore who they are without shame or constant correction. Peer groups that share similar experiences can help reduce isolation and support self-understanding.

Flexible learning options—such as project-based tasks, reduced homework loads, or sensory-friendly classrooms—can also ease the strain. Perhaps most crucially, consistent encouragement and emotional safety from understanding teachers, mentors, and families can help autistic teens feel seen, respected, and capable of thriving on their own terms.

4. Recognising Autism in Children

In early childhood, traits may appear as delayed speech, repetitive behaviours, or sensory aversions. Autistic children may experience meltdowns or shutdowns when they become overwhelmed, often as a response to sensory overload, unexpected changes, or difficulties expressing their needs.

Signs of more severe forms of autism is withdrawal, such as missing eye contact, reduced social play, or not responding to their name. However, many traits are missed, especially in girls and sensitive boys, or masked as shyness or giftedness.

Early identification and family education can create strong foundations. It can prevent or reduce early burnout, which, according to a yet unpublished study, can occur in autistic children as early as 4-10 years old. Adjustments like visual schedules and sensory-safe spaces are often effective.

5. How Many Types or Profiles of Autism Are There?

Officially, autism is now diagnosed as a single condition with varying traits and support needs. However, people may describe themselves by profiles like Asperger’s (without intellectual or physical disability), Persistent Demand or Pervasive Drive for Autonomy (PDA), non-speaking autism, or high-support needs. These distinctions help tailor support and build community understanding, even if not clinically separate.

Autism assessors are still guided by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5). It outlines three severity levels of autism that reflect how much support an individual may need:

- Level 1 – Individuals may have difficulty initiating social interactions or organising tasks independently but can function with minimal support in structured environments.

- Level 2 –Individuals often struggle more significantly with communication and flexibility and need regular support to manage daily life.

- Level 3 –level is marked by severe challenges with verbal and nonverbal communication, extreme difficulty coping with change, and high support needs throughout the day.

These levels are not fixed categories but serve as a guide to understanding the complexity of each person’s experience. Tailored support and a holistic understanding of unique traits are key to helping individuals flourish.

Developmental history continues to play an important role in autism diagnosis. Understanding the progression of a person’s behaviour, communication, and sensory experiences from an early age provides essential context for current traits; however, modern approaches offer a more flexible and responsive lens.

Contemporary practices prioritise a person-centred understanding that reflects the full diversity of autistic experiences—taking into account individual presentation, masking, gender differences, lived experience, and the evolving nature of traits across the lifespan.

6. How Many Autistic People Are There Worldwide?

The World Health Organization estimates that 1 in 100 people globally are autistic. This likely underrepresents the reality, especially in regions with limited diagnostic access.

Cultural factors, gender bias, and lack of awareness continue to hinder accurate data collection and support provision.

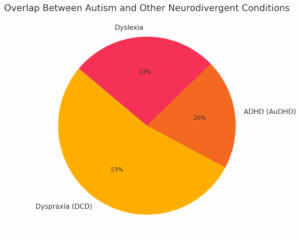

Another reason autism may be under-recognised is that it often overlaps with other forms of neurodivergence, like ADHD, dyspraxia, and dyslexia. These conditions can share traits—such as difficulties with focus, coordination, or language processing—making it harder to identify autism clearly, especially in adults.

Although many professionals now understand how common this overlap is, most assessments still focus on just one area at a time. This means some people may go through life without a full understanding of their neurodivergent profile, or without getting the right support.

7.How Does Autism Affect Employment?

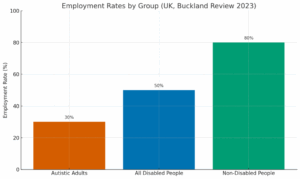

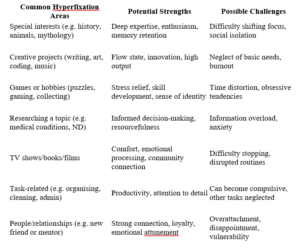

Autism can significantly affect a person’s experience of employment—not because of a lack of skill or ambition, but due to environments that often aren’t designed with neurodivergent minds in mind. Many autistic individuals bring exceptional strengths to the workplace, such as precision, deep focus, creativity, and loyalty.

However, they may face challenges with job interviews, unspoken workplace expectations, sensory overload, or unclear communication. Without the right adjustments or understanding, these barriers can lead to exclusion or underemployment. Yet with tailored support, inclusive practices, and strengths-based role-matching, autistic people can thrive—and often bring immense value to teams and organisations.

One of the biggest barriers autistic people face in gaining employment is the job-seeking and interview process itself. Traditional hiring methods often rely on social skills, quick verbal responses, and the ability to self-promote—traits that may not come naturally to many autistic individuals. Even highly skilled applicants can be overlooked if they struggle with eye contact, unexpected questions, or unspoken social cues during interviews.

Without alternative approaches such as skills-based trials, flexible communication options, or clear expectations, many talented candidates may never get the chance to show what they can do.

8. Is Autism Linked to Pathological Demand Avoidance (PDA)?

PDA refers to a profile within the autism spectrum where individuals experience an extreme, persistent anxiety-driven need to avoid everyday demands and expectations—even those they place on themselves. This behaviour is often misunderstood as defiance. It is not a universal trait in autism, but a specific profile that may require tailored approaches.

Many prefer the alternative term “Persistent Demand for Autonomy” or “Pervasive Drive for Autonomy”, as “pathological” can feel stigmatising and misleading. This profile is not officially recognised in diagnostic manuals like the DSM-5, but it is increasingly acknowledged in clinical practice, especially in the UK.

Traditional behavioural interventions can backfire with PDA individuals. Progressive strategies include collaboration, reducing pressure, and prioritising autonomy.

9. Does Autism Impact Physical and Mental Health?

Many autistic people experience co-occurring physical health conditions, which are increasingly being recognised by researchers and clinicians alike. Studies have shown higher rates of chronic fatigue, gastrointestinal issues, and autoimmune conditions among autistic individuals.

Recent findings also highlight a strong link between autism and hereditary connective tissue disorders such as Ehlers-Danlos syndromes (EDS) and hypermobility spectrum disorder (HSD). These conditions can contribute to pain, fatigue, and sensory sensitivities, making daily life more challenging.

Autistic individuals are more likely than the general population to experience mental health challenges, particularly anxiety, depression, and burnout. These difficulties are not caused by autism itself, but often arise from the stress of navigating a world that doesn’t accommodate neurodivergent needs.

Masking, sensory overload, social exclusion, and repeated misunderstandings can all contribute to emotional exhaustion and low self-esteem. Additionally, difficulties in recognising and expressing emotions (known as alexithymia) can make it harder to seek support or be understood.

Physical and mental health services often overlook or misunderstand autistic traits, which can lead to misdiagnosis, delays in treatment or inadequate care. Accessible, holistic, neurodiversity-informed healthcare is essential to addressing these complex and overlapping needs.

Progressive healthcare involves sensory-aware practices, longer appointments, and communication supports. Support strategies like neurodivergent-affirming therapy, co-regulation, and life coaching can significantly enhance self-esteem and resilience.

10. Is There a Connection Between Autism and Anger?

Anger is often misunderstood in autistic people. Autistic individuals may appear to express anger suddenly, but it’s often the result of prolonged distress, sensory overload, or communication breakdowns. Anger in this context is usually a sign of unmet needs, not a behavioural problem.

Children and adults alike may struggle to process intense emotions, especially if they are unable to communicate their experience clearly. When overstimulation builds up or expectations feel too high, anger or outbursts can be the body’s way of coping. Misunderstanding these reactions can lead to punitive responses rather than meaningful support.

Behaviour is communication. Understanding emotional triggers and offering co-regulation support can prevent escalation and is more effective than punishment or criticism. Simple changes such as predictable routines and sensory-friendly environments make a huge difference.

11. Is Autism Linked to Criminal Behaviour?

Many autistic individuals become easy targets of crime because of difficulties with interpreting social cues, trusting too readily, or struggling to identify potentially harmful intentions. Social naivety can make it harder to recognise manipulation, exploitation, or grooming—especially in adolescence or early adulthood, when a strong desire for connection and acceptance is often paired with limited experience.

In some cases, involvement in criminal behaviour may arise from trying to fit in with peers. The pressure to mask or be accepted socially can override personal boundaries or ethical understanding, particularly if an autistic person lacks full awareness of the legal or social implications of certain actions.

This is especially true for those who have experienced bullying, exclusion, or trauma, and who may see belonging as a form of survival. Sexual offences are often linked to misreading social cues, such as friendliness or interest for sexual intent or failing to recognise signs of discomfort or refusal.

Others may feel compelled to carry weapons—such as knives—not from a desire to harm, but from a heightened sense of vulnerability or previous experience of being unsafe. Anxiety, hypervigilance, and past trauma can combine to create a belief that self-defence is essential, even if the perceived danger is not imminent or the action is not lawful.

These challenges highlight the urgent need for neurodiversity-informed policing, court systems, and accessible advocacy. Without appropriate understanding and adjustments, autistic individuals may be criminalised for behaviour rooted in unmet needs, fear, or coercion—rather than intent to harm.

12. How to Know If You’re Autistic: Signs, Tools, and What to Do Next

More and more adults are starting to wonder: Could I be autistic? For many, it’s not about chasing a label—it’s about making sense of a lifetime of feeling different, exhausted by social norms, or misunderstood by others. Whether you’re newly curious or have long suspected it, recognising autistic traits in yourself can be both eye-opening and deeply validating. If you relate to any of these experiences or want to know more, connect with our team for a free discovery call or read the article for neurodivergent test.

Frequently Asked questions

What are the Benefits of Autism-Affirming Support at Work

- Clearer communication

- Better task completion

- Improved mental health

- Higher staff retention

Should Autistic People Mask in Social Settings?

- Masking can lead to burnout

- Safe environments reduce the need to mask

- Authentic connection is more sustainable

Do Autistic People Benefit from Routine?

- Routine helps reduce cognitive load

- Unexpected changes may cause distress

- Gentle transitions support flexibility

Can Autism Be Cured?

- Autism is not an illness

- Focus should be on acceptance and quality of life

Is Autism a Disability?

- Autism is legally recognised as a disability in the UK, allowing access to support and reasonable adjustments.

- However, autism does not always cause disability—this depends on personal traits and environmental fit.

- Autism is part of neurodiversity, not a flaw. Traits like pattern recognition, honesty, and creative thinking are often strengths.

How Can I Prevent Autistic Burnout?

- Burnout in autistic adults is often caused by masking, sensory overload, and constant demands.

- Reduce burnout risk by:

- Scheduling regular rest and downtime

- Spending time in calm or natural environments

- Building self-advocacy and boundary-setting skills

What Happens If There Are Too Many Demands?

- Autistic overwhelm may appear as:

- Shutdowns (withdrawal or silence)

- Meltdowns (emotional or sensory outbursts)

- Increased anxiety or fatigue

- Common triggers include loud, bright, or socially intense environments.

What Should I Keep in Mind About Autism?

- Autism is a dynamic neurodevelopmental difference, not a one-size-fits-all identity.

- Autistic people thrive with:

- Respect and inclusion

- Understanding and flexibility

- Access to the right support and adjustments